Last Updated on: 13th June 2024, 08:15 pm

Architecture & lessons learned.

Our platform, which takes part in auctions, purchases and emits advertisements in the Real-Time Bidding model, processes 350K bid requests and generates 30K events per every second which gives 4TB data every day. Because of machine learning, system monitoring and financial settlements we need to filter, store, aggregate and join these events together. As a result processed events and aggregated statistics are available in Hadoop, Google’s BigQuery and Postgres. Business requirements such as: events that should be joined together can appear 30 days after each other, we are not allowed to have any duplicates, we should not have any data losses as well as there can not be any differences between generated data outputs are the most demanding.

We have designed and implemented the solution which has reduced delay of availability of this data from 1 day to few seconds. It was possible because of a new approach and used technologies. It was essential to provide immutable streams of events to make it a good fit for our multi-DC architecture. Current real-time data flow in contrast to the previous solution is completely independent of the bidding system which produces only light events now. Because of this separation, the core system is much more stable, but also data processing has higher quality and is easier to maintain. Additionally events producing could be paused or even reprocess if it is needed.

In this post we would like to share our experience connected with building and scaling our solution in several data centers. Firstly, we would like to share a context in which we are operating. Secondly, we will focus on our data-flow. We will go through 3 iterations, the first one, in which we did the whole processing in the core platform, the second one, in which we separated data processing from our bidding platform and the last one, in which we did real-time processing of immutable streams of events.

Real-time bidding

When a user visits the website, we get a request from one of the ssp networks (we can think about ssp network as an ad exchange which is selling advertising space on the Internet in real-time). We answer in response if we are interested in buying advertising space giving our bid rate. Our competitors, other similar RTB companies, do the same. If we win the auction, we pay the second price and then we are able to emit our content for given cookie.

Currently we process 350K bid requests per second in peak from 30 various ssp networks. We have to answer the request in less than 50-100 milliseconds depending on a particular network. Our platform consists of two types of servlets – bidders (which process bid requests) and adservlets (which process user requests – tags, impressions, clicks and conversions). A tag is sent by one of our partners to help us to track user activity. An impression is created when we emit our content to him, a click – when an impression is clicked and conversion – when a user takes some action which is valuable for our customers, for example when user buys something in an online shop. What is most important, we pay for impressions but we earn money on those paid actions which means that we takeover the risk. The more optimal we buy advertising space, the more we earn.

To be able to buy advertising space effectively, we needed to store and process data, user info and historical impressions. When it comes to user info, we wanted to know which websites he had visited and which campaigns he had seen to know what we should emit him. These user profiles are created from user tags. When it comes to impressions, we wanted to know if somebody had clicked the impression, if the conversion had occurred and how much we had earned. We were able to use this data for machine learning, which meant, to put it simply, estimating the probability of a click or conversion. This probability was used for bid pricing.

The first iteration

Mutable impressions

In the first version, we kept data in Cassandra. We had two keyspaces, the first one for mutable, historical impressions and the second one for user profiles and user clicks. Related clicks and related conversions were impression’s attributes. So when the click or conversion occurred we rewrote Cassandra’s impression. The key was to find an appropriate impression to modify. In the case of a click it was quite easy, an impression id was included in the request. In the case of a conversion it was a bit more complicated. Firstly, it is difficult to decide which impression or click had caused a particular conversion. Secondly, it could always happen that the consumer would claim that a paid action was caused not by us but by one of our competitors. To simplify, we always assigned a given conversion to cookie’s last click. During conversion processing we searched for the last click for a given cookie using additional structure in Cassandra which was mapping from cookie to its previously processed clicks.

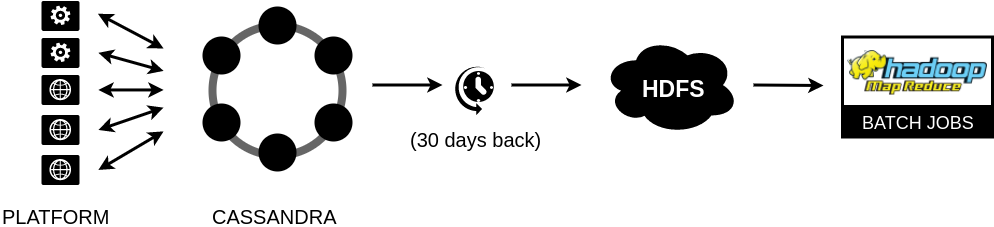

Cassandra’s data were uploaded into HDFS by end-of-day MapReduce batch jobs. Because of mutable impressions we were forced to download all the data 30 days back and rewrite HDFS content every day. Model learning based on MapReduce jobs which were run on this data (mainly as Pig scripts or Hive queries).

Drawbacks

At the beginning the solution of loading data from Cassandra was good enough for us. With time, when we were growing and we were increasing the volume of our data, end-of-day batch jobs lasted too long, mainly because we were rewriting all impressions 30 days back. Additionally, the events processing made logic of our servlets too complex but also in the case of a mistake we were almost unable to repair or reprocess it. Schemas used for data shipping were little flexible and there was a problem that we were using various formats (we had: objects in Java code, Cassandra’s columns and RCFiles on HDFS). It would be nice to have common logic for both serialization and deserialization of those to avoid mistakes connected with possible incompatibility. Finally, it would be nice to have an ability to process data using other tools than Hive and Pig (for example Crunch). We wanted to expand from one to a few DCs. Processing data locally, directly in servlets, using local Cassandra made it impossible.

Besides machine learning we wanted to use these data to charge our clients. We wanted also to be able to do our GUIs with real-time preview. In this way we were able to monitor our campaigns. Another goal was to define campaigns’ budget. If a limit was exceeded we were able to stop a campaign and not consider it during bidding and not emit new impressions. We needed easily accessible real-time aggregates. The most obvious solution was to add logic to servlets which counted statistics and updated them in Postgres. These aggregates were buffered in memory and were upserted to Postgres in batches. The solution with Postgres statistics led to some problems. The major one was connected with locks in Postgres which caused lags during requests processing. Another one was connected with some inaccuracies caused by uncommitted stats in memory. We had also inconsistencies between aggregates and detailed events on HDFS due to the fact that they were created by two independent flows. Additionally we wanted to slim down our database and introduce the rule that servlets read it only to be able to use a slave instance instead.

The second iteration

The first data-flow architecture

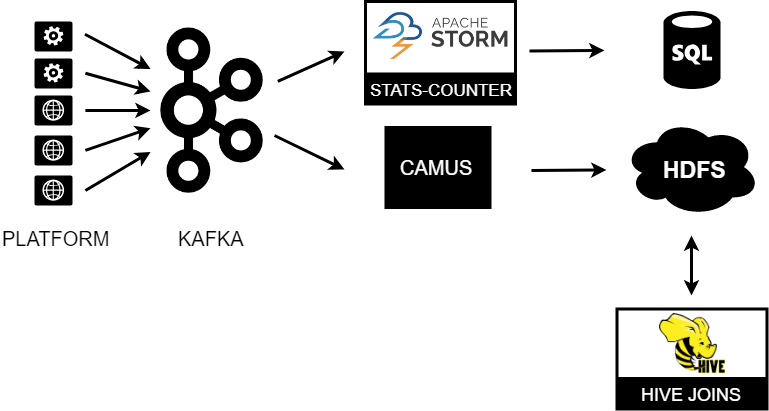

The diagram below shows high-level architecture of our first data-flow. We can see that the platform published messages on Kafka and those were read by two consumers, Camus which wrote raw events into HDFS and Storm which counted real-time aggregates available almost online in Postgres. Because of loading Kafka messages from Kafka to HDFS by Camus in batches, we had a preview of raw events with a 2-hour delay. The events, uploaded to HDFS, were merged by Hive joins. So also this time impressions were rewritten by end-of-day batch jobs and were available with a 24-hour delay.

Distributed log

Apache Kafka is a distributed log which could be considered as a producer-consumer queue. Because of Kafka we have achieved a stable, scalable and efficient solution. Stability was achieved by Kafka replication. And scalability was achieved by an ability to add new brokers to a cluster and new partitions to topics. We were able to publish and consume new types of events then, everything that we needed. Kafka holds data for a given amount of time and it does not matter if the data were consumed or not. It was important for us in case of consumers’ temporary unavailability. Due to the fact that Kafka is stateless we were able to attach new consumers and read the same data repeatedly. We used it for storing plain events on HDFS and counting aggregates but also for many other use-cases which we came up with later. Consuming data was efficient, especially that we read online data (which was just produced) from the system cache mainly.

Batch loading

Additionally we used Camus as a Kafka to HDFS pipeline which reads messages from Kafka and writes them to HDFS in our case in 2-hour batches. Camus dumps raw data into HDFS by map-reduce jobs. It manages its own offsets in log files and does data partitioning into folders on HDFS. Accordingly we had a preview on raw events with a 2-hour delay.

Avro, schema registry

We decided to use Apache Avro which is a data serialization framework and stores data in a compact and efficient format. Schema is stored in JSON format and data in stored in binary format. Schema is stored with data in one Avro file. It could define rich data structures using various complex types. What is most important, it supports schema changes so an old schema could be deserialized by a new program. We used it for transporting our data through Kafka and for storing our HDFS content.

The additional element, which we decided to add, was Schema Registry. We stored historical schemas (JSON files) for Avro serialization and deserialization. Every message which we produced was sent as a byte array with additional header which included schema_id. It is how we did events versioning. The schema registry was used in bidders and adservlets (Kafka’s producers), Camus (Kafka’s consumer) but also as “external schema” for Hive tables.

What is more, we discovered that Avro serializations and deserializations consume much of CPU time. A quick research showed that standard Avro serialization procedures include schema analysis which determines what to do with each field of Avro record and thus costs some CPU time. Our avro-fastserde lib is an alternative approach, it generates dedicated code responsible for handling serialization and deserialization which eliminates schema analysis phase and achieves better performance results than native implementation.

Real-time, accurate statistics

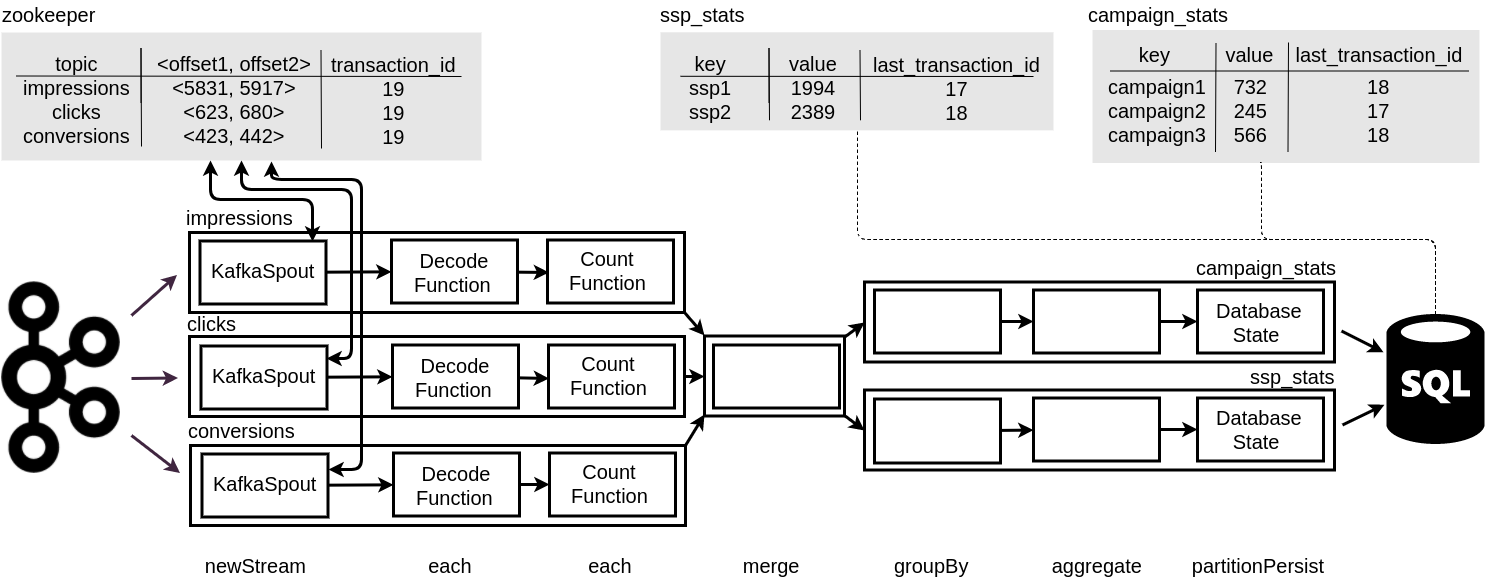

Let’s focus on statistics again. As mentioned before, we had some simple stats in Postgres but for various reasons they were not ideal. This time we made a decision to use Apache Storm. Apache Storm is a real-time computation system, which processes streams of tuples. Storm runs user-defined topologies which are directed graphs and consists of processing nodes (spouts and bolts), where spouts are sources of streams and emit new tuples, bolts receive tuples, do processing and generate tuples. Some of them could be states which means that they could persist information in various data stores. Storm executes spouts and bolts as individual tasks that run in parallel on multiple machines. It ensures fault-tolerance which means that in case of a failure, the worker would be relaunched and processing would be resumed from the stage where it was broken. By design it does one-event-at-a-time processing but its high-level API, Trident adds transactions and microbatches which help us to achieve so called exactly once processing but also good latency and throughput balance.

Stats-counter topology

We implemented stats-counter as Storm topology. Storm read messages from Kafka, deserialized it, counted stats and upserted state to Postgres. We wrote aggregates and Trident’s transaction_id(s) atomically. In case of re-batch we knew exactly which aggregate was updated and which one was not. It was possible because Trident assigns Kafka’s offset range with a transaction_id (which is committed in Zookeeper).

Thanks to it we have achieved so called exactly-once state and accurate statistics. We set micro-batches to 15 seconds so Postgres aggregates were updated every 15 seconds. The same effect could be achieved by writing current offset with aggregates. But without transactional database or other atomic operations it would not be possible.

Drawbacks

Unfortunately our data-flow had some disadvantages. As mentioned, we had almost an online view on aggregates and raw events with a 2-hour delay but detailed, joined events were still available with a 24-hour delay. Additionally Hive queries were difficult to maintain and quite ineffective for us. We were growing and our hive queries lasted too long. In a case of some failure, we were forced to run it again so we get even greater delay then. The servlets’ complex logic was still a problem. Because of mutable events it was also difficult to make some assumptions about data.

The third iteration

New approach

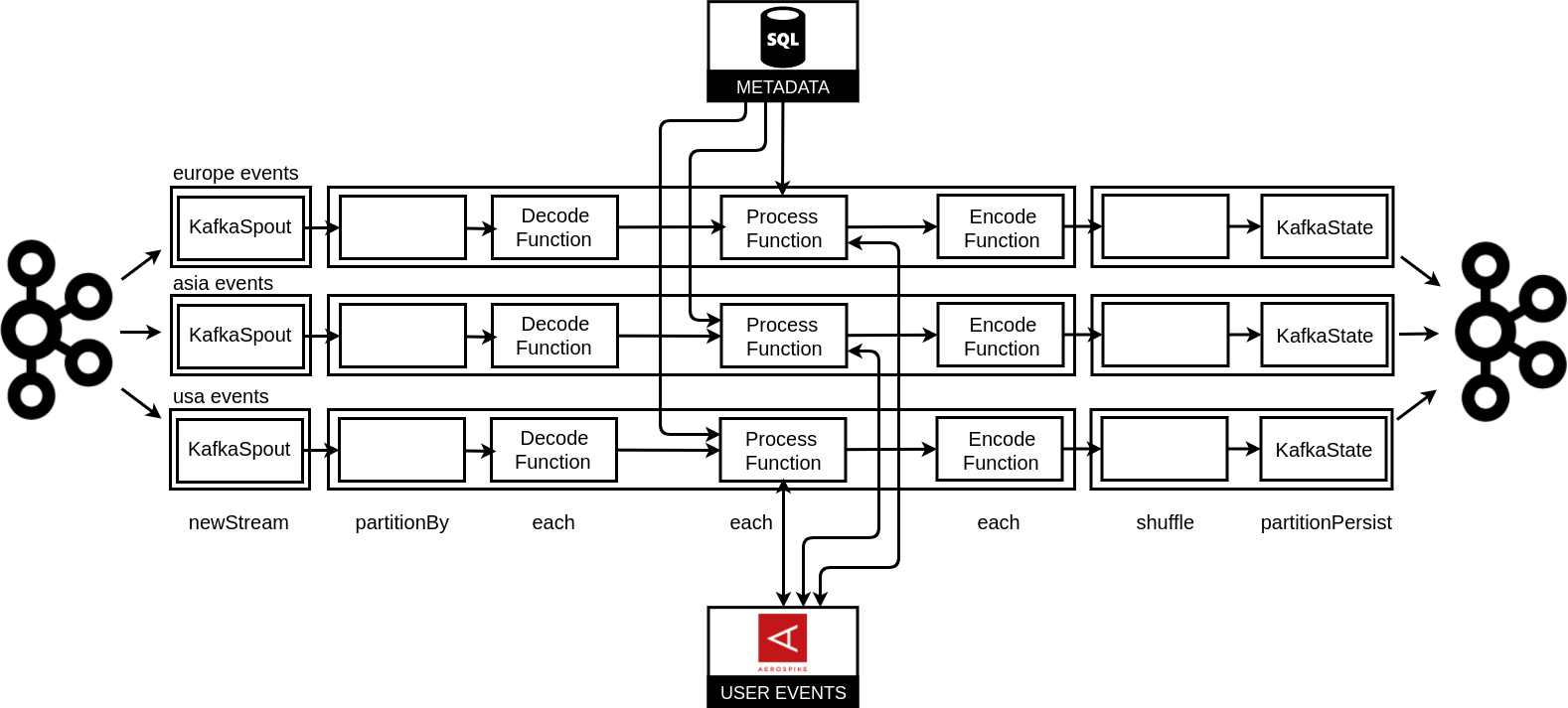

We wanted to have real-time processing and make the core system independent on complex data processing. The key was to introduce immutable streams of events, but it would not be possible without changing our schemas. Previously the related clicks and related conversions were impression’s attributes. We changed this relation, now a click contains a related impression and a conversion contains both the previous impression and the previous click. Because of this change, a once created impression was immutable forever and joining could be done during a click and conversion processing.

Data-flow topology

We had decided to use Storm. The platform produced light events and data-flow responsibility was to consume Kafka messages, deserialize and process them. At the end the generated events were serialized and sent back to Kafka (to new topics). More precisely, processing meant for us enriching information, classifying events, joining them together, counting some indicators but also filtering events and duplicating them. Because of a huge time window (a conversion could appear 30 days after an impression), we needed additional storage for storing processed events to join. We decided to use a key-value storage: Aerospike. The merging algorithm was quite similar to the one which had been used previously in Cassandra. This time we stored in Aerospike: Avro objects but also some additional mappings (from a cookie to previously processed events and from an impression to previously processed related events) to be able to do joining operations.

We can see that now we have 3 independent topologies, one topology for one DC. It is good enough for us because we process independent streams of events. Now, when we are launching the second DC in the USA, we will need additional synchronization between related DCs. For example, it could happen that impression will be sent from the West Coast and appropriate conversion will be sent from the East Coast. Those 3 data-flows are only instances of one topology implementation, run for various topics. What is worth mentioning, we decided to minimalize any possible dependencies on used framework, to be able to take our complex logic and run it with a different computation system. Thus the whole processing is done by one Storm component.

High-level architecture

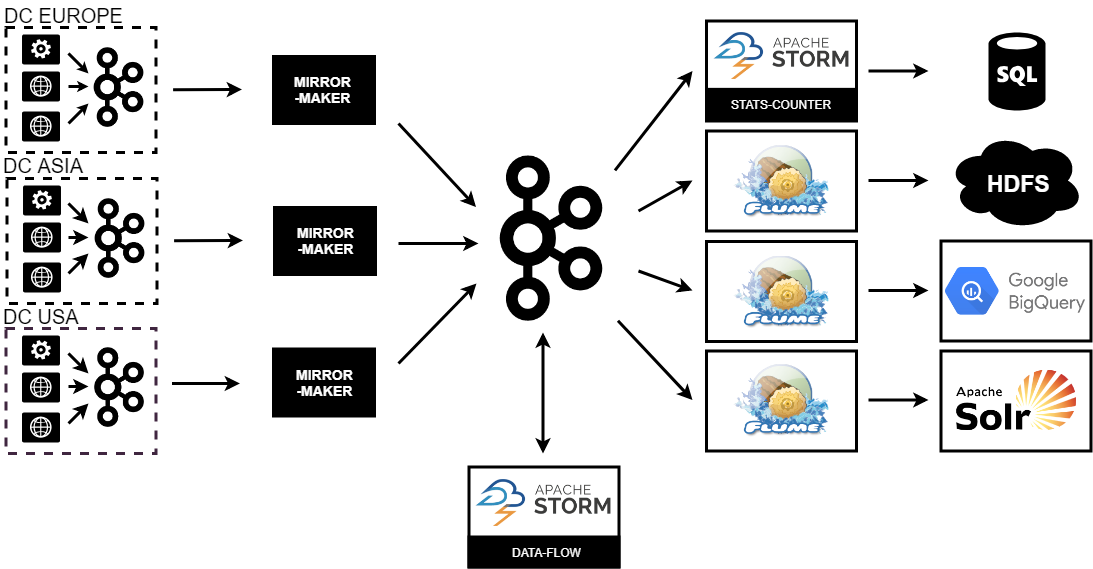

This diagram shows high-level architecture of our data-flow. The servlets wrote messages to front Kafka(s). MirrorMaker copied events from three DCs to central Kafka where the whole processing was done. The data-flow worked there and sent events back to Kafka. Further we were able to count aggregates, write generated events to Google’s BigQuery, HDFS or Solr using various Flume instances.

EDIT: A new post on this topic has just been published.