Last Updated on: 13th June 2024, 08:02 pm

Part 1 – RTB House network history

RTB House has grown from several dedicated servers in 2012 to several DC locations. Server infrastructure is constantly expanding to keep up with business needs. Currently, the platform is handling around 10 million of HTTP bid requests per second globally. Network architecture changed over the years, and migrating to L3-only approach is hopefully the last big architectural change. Here we would like to share our experiences regarding network upgrades and operations.

Network generations

First racks – switch stacking

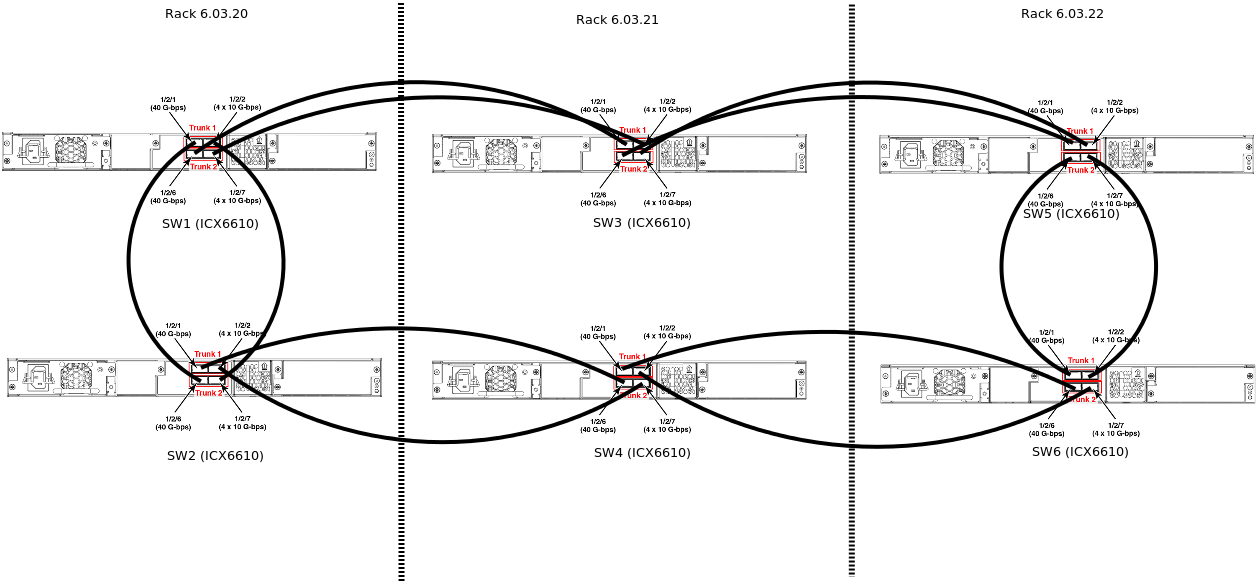

In 2013/2014, due to lacking network capacity/stability in our environment provided by an external provider, we started to deploy our own racks. At the beginning we used Brocade ICX6610 switches and we stacked them in 80Gbps loops:

This allowed full 1Gbps capacity between any host and use of VLAN separation for security purposes, for example DMZ for front servers. This setup was optimal from the cost perspective at that time, but we faced three problems:

- latency: 1Gpbs was not enough, it would take 10ms to transfer a 1MB user profile from a database (Cassandra at that time)

- scalability: inability to expand the stack beyond design, bottlenecking when connecting stacks

- availability: our stack was lacking HA/MLAG, if we lost a switch, then we would have lost servers connected to that switch

Bare-metal switches: Cumuls Linux + CLAG/MLAG

In 2015 we deployed first racks where network was based on bare metal Supermicro SSE-X3648R switches with Cumulus Linux as NOS and connected them to the existing Brocade stack using 4x10Gbps LACP uplink. At that time bare metal switch concept and DAC cables were emerging technologies and Cumulus Linux was very immature. We spammed Cumlus support with bug reports. Despite that, we achieved the majority of our goals:

- new 10Gpbs infrastructure/network cost increase vs old 1Gbps was minimal due to relatively inexpensive hardware

- 1ms time to transfer a 1MB user profile from database to the compute server thanks to DACs and 10Gbps NICs. (Those were times when, by default, the Linux distro’s kernel had a single queue on NICs, so everything needed to be tuned manually, according to https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/networking/scaling.txt)

- availability: MLAG allowed to connect the servers to two redundant devices, but this implementation was not perfect:

- MLAG LACP in a fast mode could wait up to 3-4 seconds to disable interface in a group, which caused some of our server cluster nodes to flap and was very annoying.

- Cumulus MLAG immaturity caused problems that we were unable to reproduce (for example from time to time a pair of switches stopped seeing each other via peerlink).

VXLAN BGP EVPN

Pure L2 network can not be scaled up indefinitely. As racks rows were added, we were looking for a way to expand the infrastructure and make it more stable. Cisco published interesting book: Building Data Centers with VXLAN BGP EVPN and few months later Cumulus Linux presented a new release, adding EVPN functionality. We saw VXLAN BGP EVPN as a potential solution for our scaling and stability issues. The release was quickly deployed on production environment and basic EVPN set up using Cisco guidelines. Leaf switches encapsulated L2 into VXLAN tunnels and SPINE switches become L3 routers. This design eliminated potential L2 loops at the second and third network layers. Our conclusions regarding VXLAN BGP EVPN network architecture after several years of experience (on the most cost-effective devices – mainly Broadcom Tomahawk based) are as follows:

- stability/visibility/debugging is lacking: whenever a network device failed, we could observe strange things, for example random switch started to announce network layer reachability information (NLRI) that was bogus. We could not reproduce this problem, and it occurred in production several times.

- depending on the silicon chip model, device behaviour could differ, and lack of chip feature could hit you hard

- in real life VXLAN BGP EVPN is hard to extend and modify in production.

- In one case, we tried to enable ARP/ND suppression and it blocked keepalived traffic

- When we enabled ARP/ND suppression for most of the devices, the network became very unstable suddenly and without apparent reason. The only way to quickly recover was to roll back configurations and restart all switches in the datacenter. This instability appeared only when it was deployed at scale in production. As you can imagine, this was not a good day. ?

- Our experiments with EVPN Routing had shown that it works well on a Vagrant test environment, but when we put the config on a physical device, chip limitations kick in, and the entire carefully planned setup is doomed to fail.

Q: What are the practical limits on the size of a flat L2 network?

After adding racks after racks, we ended up with a basic VXLAN BGP EVPN + MLAG deployment, where the largest VLAN/VXLAN had:

$ arp -an | grep 'on bond0' | grep -v incomplete | wc -l

1435

MAC addresses.

To be able to accommodate so large ARP table on the host, some sysctl’s need to be tuned up. Our production settings are as follows:

net.ipv4.neigh.default.base_reachable_time_ms = 1200000

net.ipv6.neigh.default.base_reachable_time_ms = 1200000

net.ipv4.neigh.default.gc_thresh1 = 8192

net.ipv4.neigh.default.gc_thresh2 = 32768

net.ipv4.neigh.default.gc_thresh3 = 65536

As you can imagine, to grow more, we are in need of a network architecture that is:

- more scalable

- easy to manage/debug/deploy

- able to run on the most cost optimal switch silicon chips (like Broadcom Tomahawk)

- keep current VALN/VXLAN separation between bare-metal servers

It was decided that new servers should be connected to the switches in the “L3” way to avoid broadcast domains. We will keep current VLAN/VXLAN separation in old “L2” part of network and replace it with VRF in “L3”. Then we will connect those “L2” and “L3” networks together by as many uplinks as needed without the need to migrate entire locations to the new architecture. If you are interested in the implementation details, please continue to the next posts.

P.S. Alternative solutions

- EVPN Routing was too complicated for us, ASIC limitations are hard to predict, and when you need a feature on an entire DC, it may require an upgrade of devices.

- External router connecting multiple L2 networks will not be able to handle the required volume of traffic.

- Simple L3 on native VLAN will break network separation we relay on for bare-metal servers.